Lauren Schwartz Roth, Ph.D.

Mental Health & Behavior Research Programs

Foundation for Prader-Willi Research

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a complex genetic condition involving a range of physical, mental health, and behavioral characteristics. This guidebook has been prepared for families of people with PWS and for others who provide clinical, behavioral, and educational support. Mental health challenges are common in PWS, and for many families, they are a top concern. Research shows that people with PWS are at higher risk for specific mental health challenges, including “affective disorders” (depression, bipolar disorder) and psychotic symptoms (see the glossary for more information on these conditions and symptoms). Because people with PWS may present with symptoms that are unique to the syndrome, this guidebook was created to highlight the various ways people with PWS may present with mental health struggles. We also include initial steps toward obtaining effective care because the course and treatment of those symptoms often require special consideration. The information presented in the guidebook was gathered from extensive one-on-one interviews with caregivers whose loved one with PWS has experienced mental health and severe behavioral challenges. Additionally, experts in the fields of mental health and PWS were interviewed individually regarding these issues. We gratefully acknowledge their contributions to this summary.

It is important to note that although individuals with PWS have a variety of behavioral challenges, including anxiety and temper outbursts, this guidebook focuses mainly on serious mental illness in PWS because there are few resources for parents in this area.

In this podcast, Lauren Schwartz-Roth, clinical psychologist and mom to a young adult with PWS, shares how to identify and treat serious mental health issues in our loved ones with PWS.

Information for this guidebook was obtained from reviews of current research literature on mental health issues in PWS, from one-on-one interviews with parents whose loved one with PWS has experienced serious mental health challenges, and from interviews with PWS mental health experts. All interviews occurred in 2019–2020 and were recorded and transcribed. The transcriptions were then analyzed by the study investigator and research project coordinator for themes and consistent patterns noted across interviews. Several areas were highlighted in the interviews and are discussed in the following pages, including early signs of mental health issues and the challenges of identifying, diagnosing, and effectively treating symptoms. Finally, parents and experts shared information about useful strategies for helping to decrease symptoms and ways to best support parents through this process.

Parent caregivers whose loved one with PWS has experienced serious mental health challenges were invited to participate in the study. Fifteen parent caregivers volunteered to be interviewed for the project. This project focused on families living in the United States who had a loved one with PWS over the age of 10. See Table 1 for details about PWS family participants.

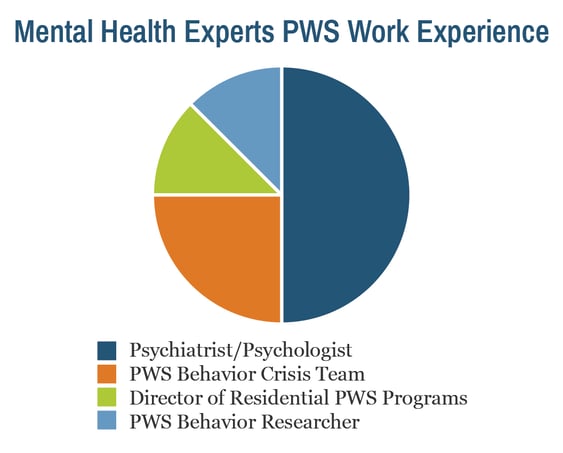

Health care providers and researchers with established and extensive experience in PWS mental health and behavior were recruited to be part of the study. Eight experts in PWS mental health participated in one-on-one interviews for this project. See Table 2 for details.

|

Fifteen (15) PWS caregivers were interviewed |

|

|

Variable |

|

|

Age of person with PWS, mean (SD) |

21 (5.84) years |

|

Age range |

12-32 years |

|

Sex of person with PWS |

|

|

Male |

10/15 (66.7%) |

|

Female |

5/15 (33.3%) |

|

PWS genetic subtype |

|

|

UPD |

10/15 (66.7%) |

|

Deletion |

5/15 (33.3%) |

|

Living situation for person with PWS |

|

|

Group home/residential facility |

3/15 (20%) |

|

Living at home with parents |

12/15 (80%) |

|

Interviewee’s relationship to person with PWS |

|

|

Mother |

13/15 (86.7) |

|

Father |

2/15 (13.3) |

|

Eight (8) PWS mental health experts were interviewed |

|

|

Experience working in PWS, mean (SD) |

19.25 (10.66) years |

|

Years of experience working in PWS, range |

5-30 years |

Both caregivers and mental health experts interviewed highlighted several consistent themes across interviews related to early indications and potential triggers for mental health challenges. These are discussed below.

The most challenging age period in terms of behavior and mental health symptoms was reported generally to start in early adolescence, at approximately 12 years of age, with 75% of those interviewed reporting significant mental health issues starting after age 12 years. Four (~25%) of the caregivers interviewed reported severe mental health issues starting before age 10 years for their loved one with PWS.

Most caregivers noted that in looking back a few weeks before the onset of serious mental health issues, they noticed changes in their loved one’s sleep pattern, changes in eating (usually less interest in food), and more behaviors than usual reflecting agitation and/or higher anxiety. Some parents also noted in retrospect that their child was isolating more and was not as interested in engaging in activities or social activities that they previously enjoyed (see Table 3 below).

One expert stated, “people with PWS generally eat and sleep well, so if you see changes here, that is a signal something might be going on.”

Examples of specific triggers for significant mental health symptoms listed by the parents included a change in an aide, teacher, or home caregiver; sibling leaving for college; death or serious illness in a loved one; or moving homes/changing schools or programs. It’s important to note here that while some of these triggers might be expected to cause a mental health crisis (e.g., death of a loved one), others represent situations that would not normally be associated with a significant mental health crisis (e.g., being assigned a new aide at school). This underscores the mental health sensitivity of some individuals with PWS to seemingly small changes in their lives.

Some parents reported that during times of change or heightened distress, their child started to hear voices or, for those who had imaginary friends before, these “friends” started saying mean or scary things to them. Many parents and professionals we interviewed suggested asking specific (but not leading) questions of your loved one if you suspect they are struggling more and might be having some symptoms of mental illness. Most people, including those with PWS, are not likely to volunteer this information. Parents may want to be ready with a “casual” response if their loved one with PWS reports hearing voices or if they answer yes to the questions below. The following are some suggestions for ways you can ask your loved one about serious mental health symptoms:

Questions to ask if you suspect they may be experiencing hallucinations (hearing and seeing things that others do not):

- "I notice you have been talking to yourself. Do you ever hear someone answering back?"

- “Do you ever think you hear people talking to you? Not us (family) but people you don’t know who might say things to you or about you? Does it ever make you feel scared or angry?”

- "Have you been seeing things that other people do not see? Do the things you see scare or bother you?”

Questions to ask if you suspect they are having delusions (ideas or thoughts that do not seem to be part of reality/realistic):

- “Do you ever think people are watching you or talking about you?” (Check to see if this is something new or different; you are looking for a change from their typical behavior).

- "Do you feel like you have special powers that other people don't have?"

It is helpful to come up with a common language to describe symptoms and to use terms that people with PWS will understand and find accurate. The experts interviewed also mentioned that because people with PWS tend to want to please their parents, especially their moms, they may be less likely to admit to having psychiatric symptoms (e.g., hearing voices) if their parents are in the room during that part of a medical or psychiatric assessment. Thus, some PWS mental health professionals prefer to conduct part of the assessment without parents present. However, this needs to be navigated carefully since persons with PWS are prone to confabulation (when a person makes up a story to fill a gap in memory or for other reasons) and may not provide an accurate representation of their symptoms without input from their parents. If the mental health professional is not familiar with PWS, this may be problematic. It is important that the person doing the assessment of your loved one confirms the information gathered with the parent and/or caregiver most familiar with the person with PWS.

|

What Should You Look For? |

|

|

Look for changes in the person from their usual behaviors

|

|

|

Special Considerations in PWS |

|

|

Many of the families and experts interviewed noted that sleep was particularly important in PWS in terms of mental health and wellness. Almost all caregivers noted that their loved one slept “a lot,” and 73% of caregivers reported that their loved one still required at least a 1-hour nap during the day to function optimally, even as adults (see Table 4). Additionally, the majority of caregivers and experts noted that sleep patterns usually had changed notably in the days and weeks before any significant new mental health event. For example, caregivers stated that before their loved one developed serious mental illness symptoms, “naps just stopped.” Several caregivers shared that their loved one with PWS “started staying up later and later at night” or “they were just up and down all night long.”

Not getting enough sleep for a period of time, especially in combination with a stressful situation, was also identified as a trigger for greater behavioral challenges and possibly for more serious symptoms in someone vulnerable to a psychiatric condition. Many parents and experts emphasized the importance of people with PWS having a regular and consistent sleep schedule to help to maintain their mental wellness, encouraging at least 8 to 9 hours of sleep per night, or more if that is their baseline.

One caregiver presented a case in which their loved one with PWS appeared to be having auditory hallucinations (hearing voices) which turned out to be related, in part, to an undiagnosed sleep disorder (narcolepsy). The experts noted that although this was not typical, it gave strong support to the recommendation that individuals with PWS presenting with a change in mental health status also be assessed for undiagnosed sleep disorders as part of a full mental health evaluation.

|

Summary of Sleep Patterns in 15 Individuals with PWS |

|

|

Hours of sleep per night, mean |

9.36 hours |

|

Hours of sleep per night, range |

8-12 hours |

|

Napping regularly (of at least 1 hour) |

11/15 (73%) |

Distinguishing between typical “PWS behaviors” and serious mental illness (which requires intervention) was considered a significant challenge for caregivers and mental health professionals. Many stated that at the time of the mental health crisis, the behaviors and symptoms often “just look like PWS but worse.” One caregiver reported, “It took us a surprisingly long time to say, gosh, this is mental illness, and we’re not uneducated about these things, but we just didn’t quite see it.” Many other caregivers echoed this statement.

It can be helpful to start to track behaviors in your loved one with PWS if you suspect there might be some changes in their mental health. Some parents simply put check marks on a calendar or notepad indicating the frequency and/or intensity of symptoms they wanted to track, such as anxiety, anger outbursts, or sleep patterns. This could be especially useful information to bring as part of an assessment. Additionally, there are a number of behavior trackers and apps that can be used to gather information on behaviors and symptoms directly on your smartphone or tablet.

The PWS mental health experts who were interviewed underscored that if a person appears to be experiencing symptoms of mental illness, a thorough medical and psychiatric assessment is key. Treatment of a mental health issue in someone with PWS should start with a detailed history and examination to determine possible diagnoses as well as to eliminate other possible causes, including medical causes such as infection, seizures, or a medication reaction. Ideally, it is best to try to find a provider who has some experience working in intellectual/developmental disability and mental illness.

Both parents and experts talked about the benefits of early identification of mental illness symptoms in PWS. As with other mental illness conditions, the longer a person has undiagnosed and untreated symptoms, the longer it can take to reduce and resolve the symptoms. One caregiver shared, “If we had caught it right away, they could have pulled her out of it a lot sooner.”

Parents reported that when they became concerned that their loved one needed assessment for a potential mental health issue, consulting with their loved one’s primary care provider was often the first step in this process. However, what was really needed was a PWS specialist. This was a big challenge given limited resources as well as the limited number of health care professionals who are familiar with PWS. Overall, this is one of the greatest challenges to caring for people with PWS and mental health symptoms. Many parents recommended, especially for high-risk individuals, getting a local mental health provider involved with the person with PWS early on (consider early adolescence) in anticipation of potential mental health symptoms later because there are long waiting lists. This way, they can get a baseline and an opportunity to learn about PWS if/before there is a crisis.

➜ Early in adolescence, parents may want to enlist the child’s primary care physician in helping them identify a local mental health professional who can work with their loved one with PWS. Find a mental health provider who is willing to learn about PWS, since many will not be familiar with this rare syndrome.

At this point, it is a good reminder that all of the caregivers interviewed for the guidebook volunteered to participate in the project because their loved one with PWS had had serious mental health challenges. This is a subset of the population, and not all people with PWS will have these difficulties!

For more information on some of the conditions and symptoms mentioned below, please see the glossary.

The mental health and behavior difficulties parents discussed ranged from behavior challenges with high levels of anxiety and anger or aggressive outbursts to serious psychiatric issues such as psychosis and mania symptoms. The most common mental health diagnoses for people with PWS that parents and experts discussed during the interviews were bipolar disorder, psychosis, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (see Table 5).

Focusing on some of the most serious psychiatric issues, caregivers and experts reported psychotic symptoms in people with PWS reflective of auditory hallucinations (e.g., “hearing voices, or someone talking to me”) and/or delusions (e.g., a fixed false belief, such as “there is an animal that lives in my room”). People with PWS who experienced hearing voices reported that the voices were sometimes neutral or friendly in tone, but other times, they were unfriendly or scary. The onset of the voices for many with PWS was often related to a stressor or change in their environment, as mentioned in previous sections. Usually, the neutral/friendly voices did not warrant treatment but rather assessment and monitoring. For those with PWS who experienced “scary” or negative voices, assessment and treatment with appropriate medication were usually required to prevent further escalation and deterioration. It is important to point out that individuals with PWS who are experiencing psychotic symptoms do not have a chronic decline in function as is typically seen in schizophrenia. The auditory symptoms (“voices”) seen in PWS can also fluctuate with stress and other life transitions, but experts and families reported that they tend to be well treated with medication. It was emphasized by the mental health experts and caregivers that once the correct diagnosis and a period of appropriate treatment are obtained, there is typically a return to baseline function for the person with PWS. One parent stated, “they come back to you, they really do.” This sentiment was echoed by many other parents in the study.

Dr. Anthony Holland, a renowned PWS psychiatrist, noted in his paper on the mental health of people with PWS that individuals with PWS can struggle with depression and/or mania symptoms. Dr. Holland noted that some individuals with PWS will have fluctuations of mood from high (manic-like symptoms) to low (depressive symptoms), similar to what is seen in bipolar disorder, but what is unique to PWS is that there is also likely a significant increase in some of the core PWS behaviors, such as food seeking, repetitive behaviors, skin picking, oppositional behavior, or tantrums either preceding or co-occurring with psychiatric symptoms. Individuals with the uniparental disomy (mUPD) genetic subtype of PWS are more likely to develop bipolar disorder–type symptoms, and this may co-occur with psychosis.

Last, it is important to note that not all mental health crises were accompanied by hallucinations or delusions. In some cases, typical PWS behaviors (temper outbursts, rigidity, aggression, depression) escalated to a point of crisis, and intervention to address these symptoms was usually required.

|

Reported PWS psychiatric diagnoses and extreme behaviors (N=15 participants) (Note: Most individuals had more than 1 diagnosis) |

|

|

Anxiety |

5 |

|

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) |

5 |

|

Bipolar |

6 |

|

Psychosis/Delusions |

8 |

|

Autism spectrum disorder |

1 |

|

Talk about suicide |

5 |

|

Suicide attempts |

2 |

|

Aggressive/Violent behavior |

6 |

|

Running away/“Eloping” |

4 |

To date, there has not been a lot of information about suicidal ideation (talking about suicide) or suicide attempts in PWS. We also looked at data from the Global PWS Registry to shed further light on this topic as it relates to serious mental health issues in PWS. A review of the data from the Registry indicates that 15% of caregivers (note a total of 618 caregivers participated in this Registry survey) reported that their loved one with PWS had talked about suicide when they were upset or distressed, with the average age of the person with PWS being 16 years. In addition, 4% (24/646) of caregivers who completed the survey in the PWS Global Registry reported that their loved one had made a suicide attempt. Two out of the 15 caregivers who participated in the current interview study reported that their loved one had made a suicide attempt. Actual suicide attempts by a person with PWS are a rare occurrence, and while talking about suicide is not common, it does occur in PWS. If persons with PWS talk about suicide and have a specific plan to harm themselves, this should always be taken seriously, and caregivers should contact a health care professional and have them assessed right away.

Serious mental health conditions, including depression and bipolar disorder with psychotic illness, can affect people of all PWS genetic subtypes (deletion, mUPD, and imprinting defect) at higher rates than the general population. However, research and clinical studies show that serious psychiatric difficulties most commonly affect people with PWS due to the mUPD or ID forms of PWS. Estimates vary, but recent studies suggest that approximately 60% of people with PWS due to mUPD may develop psychotic symptoms during their lifetime. This typically occurs in early adulthood but can start as early as the teenage years. Individuals with the deletion subtype of PWS are also at elevated risk of serious psychiatric issues compared to the general population, but their risk is lower than for those with mUPD. For individuals with deletion subtype, if psychosis symptoms are seen, it is often, but not always, in the context of a clinical depression.

➜ People with PWS by mUPD have a very high risk for developing psychiatric symptoms, BUT, people with the deletion subtype also have an elevated risk compared to the general population.

Several of the families interviewed reported that their loved one with PWS was hospitalized for mental health difficulties. About half of the individuals with PWS had had inpatient treatment for their psychiatric symptoms. Many of the families and experts shared their concerns about people with PWS being treated and hospitalized by health care providers who may not understand the unique aspects of a person with PWS. Families discussed the importance of providers and staff on inpatient units being willing to be educated about PWS, especially in regard to hyperphagia and the need for food security and boundaries, and how this might show up on an inpatient unit.

Here are a few specific recommendations from the expert and family interviews:

➜ Many families stated, “just keep trying until you find the right person and place for your loved one to get treatment.”

The caregivers interviewed for the study tended to be very positive about the use of medications to help their loved one struggling with mental health issues. This was especially true if their loved one had experienced signs of serious mental illness, such as hearing voices or having symptoms consistent with bipolar/mania disorder (e.g., pressured or confusing speech, high levels of agitation, sleeping or eating significantly less).

One caregiver said: “Don’t be afraid to try medication. They may have to try a few different ones before you find the right one. But honestly, it really can improve their quality of life a lot and yours. “

Experts said: “if there are serious psychiatric symptoms (hallucinations, mania), don’t wait too long to try medications.”

Both caregivers and experts interviewed emphasized the importance of having a psychiatrist, not a general medical provider, evaluate and prescribe medication for your loved one (if needed). Several experts stated that they really needed to have a psychiatrist to understand the ways psychiatric medications work and how they might interact with other medications and other aspects unique to PWS.

It was strongly recommended by all of the PWS mental health experts who were interviewed to “start low and go slow” when starting or changing any psychiatric medication. Some experts stated that even subclinical doses can be helpful, especially in younger people with PWS, and that psychiatric symptoms in PWS respond well to treatment with medications, but often at lower doses than what might be used in the general population. Several of the experts expressed concern about the number of psychiatric medications individuals with PWS are taking, also known as “polypharmacy.” Particular concerns were shared regarding the increased risk of negative drug interactions and adverse effects when individuals take multiple psychiatric medications. They encourage families to discuss any concerns in this area with their loved one’s health care provider. The types of medications caregivers reported their loved ones were taking for mental health issues are listed in Table 6. Note that many were taking more than one medication, and a few of the medications that were helpful for some of the individuals with PWS caused significant and difficult adverse effects for others and had to be discontinued.

During the interviews, caregivers were asked to rate the “helpfulness of medications” for their loved one with PWS on a scale of 0 to 10. The results indicated that overall, most caregivers found medications to be very helpful for their loved one, with the mean (average) rating being an 8 (see Table 6).

Caregivers said:

“[name] was in the hospital several times for different psych symptoms as a teenager. [name] was on medications, which were helpful for a while. Then we tapered down the medications, and nothing ever happened again until several years later when [name] was 18 or 19, and now we still battle it at times, but we know how to deal with it, with the medications. And we now have the medications at home, so we don’t have to go in for them. That has been really helpful. We also decrease all stimulation and activity for a while, too. And since doing this, we’ve never had another full-blown psychosis and no trips to the ER. As an adult, [name]’s now on daily medication, which really helps. I can tell if [name]’s not taking the medication from the way he’s acting, pretty much immediately, and we can stop it with getting [name] back on the meds.”

“As a young teen [name] started having manic-type symptoms, agitation, not sleeping, and talking A LOT. We tried several different medications, til we found the right one. The doctors now also have me give Ativan for a few days if we see a flare-up coming, and it takes away the manic situation. It does knock [name] out for a time, but this medication seems to get [name]’s brain back to reset and calm. We give a very low dose for about 3 to 5 days, and it can bring [name] out of it without going into the big full-blown psychosis. I’ve done it three times since then, and [name]’s never been back to the hospital.”

|

Reported PWS psychiatric medications (N=15 participants) (Note: Many were taking more than one medication) |

|

|

Mood |

|

|

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) (e.g., Celexa, Lexapro) |

5 |

|

Wellbutrin |

1 |

|

Buspar |

1 |

|

Antipsychotics |

|

|

Risperdal |

8 |

|

Seroquel XR* |

1 |

|

Aripiprazole* |

4 |

|

Mood stabilizers |

|

|

Lithium |

4 |

|

Depakote |

1 |

|

Topamax |

1 |

|

Naltrexone |

3 |

|

Beta blocker (e.g., Metoprolol) |

1 |

|

Gabapentin (for anxiety) |

2 |

|

Guanfacine |

3 |

|

Sedative (Clonazepam) |

2 |

|

Cannabidiol (CBD) oil |

2 |

|

Rescue medications (used as needed in a flare-up or mental health crisis) |

|

|

Sedatives (Ativan, Valium/Xanax) |

4 |

|

Increased “rescue dose” of Risperdal |

2 |

|

Helpfulness of medication (0-10 scale), mean (SD) |

8 (1.31) |

|

*These medications, although very helpful for some, were mentioned in the interviews as having caused difficult adverse effects for several individuals with PWS, particularly agitation or increased anger. |

|

In the last decade, some direct-to-consumer tests have appeared on the market that claim to be able to help select psychiatric medications for your loved one. The PWS experts were asked about the usefulness of this approach. It was felt by the group that this might be useful but many of these tests tend to overpromise. Some of the experts felt that information gleaned from these tests, when used in a clinical setting, could be helpful in some cases when the person has tried several different medications that have not been effective or when the person is not responding to the typical treatment approaches. However, other health care providers felt that the tests do not at this time offer clinically significant information. All agreed, however, that trying these tests at home was less useful than was using them in collaboration with a trained medical provider.

Psychotherapy: Caregivers and mental health experts were asked about other approaches to assist with mental health challenges in PWS. Psychotherapy was mentioned as being helpful for many individuals with PWS, but with some caveats and guidelines. A personal connection and good rapport with the therapist were listed as key factors for success in therapy for a person with PWS. Caregivers mentioned that therapists who had experience working with individuals with intellectual disability and cognitive differences were also crucial. Key personality characteristics for the therapist working with the person with PWS, according to caregivers, were the ability to be “structured but flexible” and not rigid or likely to get into power struggles with the person with PWS. Finally, caregivers mentioned that it was very helpful for their loved one to work with a therapist who genuinely seemed to like and appreciate all the great aspects of that loved one’s personality.

Current evidence-based psychotherapies, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), can be used with people with PWS, but the success of such treatments depends on the person with PWS being able to have good abstract thinking abilities and a willingness to practice the skills taught in therapy between sessions. Unfortunately, caregivers and experts reported that most people with PWS had difficulty with these approaches and were not successful. However, they reported that many people with PWS did benefit from supportive, problem-solving psychotherapies as a place to process their emotions and stress with someone other than a parent/caregiver. Additionally, in this type of therapy, it may be possible for the person with PWS to work with the therapist on problem-solving strategies and to learn some concrete coping strategies, such as breathing, relaxation techniques, and journaling to help manage their emotions and stress. Some families also found that mindfulness apps (such as Headspace and Calm), particularly those with kid-friendly meditations or guided imagery, could be very helpful for the person with PWS. However, caregiver cueing was almost always needed to help the person with PWS use these coping strategies in their daily lives.

Highlights from responses on non-medication approaches to mental health challenges include:

Environmental Interventions: Many of the mental health experts stated that it is useful to look at potential environmental contributors to mental health and behavior struggles. Sometimes, modifying the environment can help decrease behavioral and mental health symptoms. This was suggested as an early first step in trying to address behavioral challenges in your loved one with PWS. The benefits of this were also echoed by many of the caregivers.

Figuring out ways to make home, school, and/or work less stressful for the person with PWS is a good starting point. Interviewees recognized that this might be challenging to do, but they felt it was important to carefully review potential sources of stress, keeping in mind that these may include things that would not necessarily stress a person without PWS. It was also pointed out in the interviews that for many people with PWS, once they start experiencing mental health challenges, certain environments that were previously manageable became too agitating or stimulating, and changes needed to be made. Parents suggested that trying to create regular routines at home and school that can bring comfort and predictability and decrease stimulation were helpful. Sometimes, these changes were needed temporarily, and sometimes, longer-term modifications were required to maintain mental wellness. Parents and experts noted the value of trying to be very consistent with sleep and rest patterns for the person with PWS and decreasing school demands and social activities until mood/behavior seemed to stabilize.

Highlights from responses on environmental interventions include:

One caregiver said: “He had been doing really well in school, so we just expected that would continue. But high school was very difficult, and the stress of trying to keep up was too much. We started to see more and more mental health symptoms. I finally realized that I needed to lower my expectations and prioritize changes that would reduce his stress if we were going to make it through.”

Finally, the majority of the caregivers and the experts highlighted the importance of having very consistent food security during times of mental health and behavioral challenges. However, one expert also mentioned that this was not the time to start a strict new diet or routine because it could be too stressful during a vulnerable time. The suggestions from the experts were to “tighten up” on existing routines and increase security around food. This can help people with PWS feel safer and less anxious with food being secured and having consistent routines and schedules for meals.

During the interviews, many comments and stories were shared by PWS caregivers and the mental health experts about how food security and mental health issues overlapped. Following are a few examples:

Caregivers said:

“I wanted to teach [name] self-control. I had to realize this was not possible and likely causing more stress. [name] is calmer now with food locked up, and it does reduce the anxiety. We found that when anxiety and aggression were worse, that usually meant food security was lacking in some area like school.”

“[name] was doing so well; we were slow to recognize the stress it (lack of food security) was causing. [name] has an IQ on the higher end for PWS, so I thought we could teach [name] to manage the food, but I came to realize that even if your child with PWS is doing well, they need those boundaries around food.”

“I was really trying to help [name] mature, so I was giving her some freedom. We weren’t locking up food because it felt like [name] would never learn to be independent if we did that. [name] is so smart. But this actually was creating so much frustration, and that stress was contributing to her mental health and anger problems. I learned that lesson the hard way.”

Mental health experts said:

“Not locking up food for some kids makes anxiety at intolerable levels, especially if they are vulnerable; this can trigger a mental health crisis.”

“The person with PWS often wants the greater food security even if they can’t articulate it. It often helps them to feel calmer; they can be silently suffering with the food calling to them.”

Other non-medication strategies: Other non-medication approaches that were reported to be helpful by PWS caregivers were using weighted blankets (this was mentioned a lot!), engaging in hippotherapy (specialized horseback riding) or other sensory-calming activities, and the use of scripted relaxation recordings (try Calm or Headspace apps with kid-friendly recordings).

Some parents found supplements to be helpful for their loved one in terms of decreasing stress or anxiety. Two caregivers reported that they thought CBD was helpful. However, it was strongly recommended by parents and mental health experts that the use of any supplement, including CBD, should be discussed with health care providers because there can be adverse interactions with other medications and potential serious toxicity issues if not closely monitored.

At the end of the interviews, the PWS caregivers were asked about the most important things they thought parents can do to support their child through a mental health crisis, as well as about things they wish they had known before going through this. Here are some of their thoughts about this:

“Reach out early and get support if you have any concerns, don’t wait or think it’s just a phase. Catching it early can make it easier to treat and easier for them to come back to their normal self. Don’t be afraid to just say to their doctor “I’m seeing this …. It might be nothing, but ...”

“I think it is really important for parents to be a team; when you are going through something this stressful, you need someone to partner with you to manage these issues even for your own mental health. If this isn’t the other parent, then find a friend or other PWS parent who can be your ‘partner’ to help you think through things, make decisions, bounce ideas off, and listen to you vent. This can really really help.”

“I think remembering that it is temporary. One of the hardest things for a parent is to watch their child go through something like this, because there is a fear that this is the new normal. It took a few years to get it all sorted through, but it was worth it. At 23 years old, we have the right medication, good support, and a stable living situation for [name]. His mental health is really good. Please make sure you tell the other parents they do come back to you, that sweet kid is in there.”

“A doctor who knows PWS told me about the whole hypothalamus thing in PWS and how it’s involved in regulation of emotions. She explained that our kiddos do not have that regulation, so that when they get upset they just go from 0 to 100. So now, I remind myself that my child’s brain works in this way, it’s not their fault, it’s how they were made, you know. Learning that was like a golden nugget of understanding for me. That doesn’t mean I am not going to give consequences and work with my kid to help with their behaviors, but I can better understand that they are trying their best and they have a lot working against them. “

We are grateful to the Moriah Foundation for providing funding for this project.

We want to thank all the wonderful and dedicated PWS caregivers for agreeing to participate in this important study and sharing their deeply personal and difficult stories.

Thank you to the FPWR team for their helpful contributions, discussions, and edits: Susan Hedstrom, Theresa Strong, and Caroline Vrana-Diaz.

Finally, we greatly appreciate the community of PWS mental health experts (listed below) who were incredibly generous with their time giving interviews and providing feedback on the PWS Mental Health Guidebook.

PWS Mental Health Expert Contributors:

Laura Bennett Murphy, Ph.D.

Division of Pediatric Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, University of Utah

Utah PWS Clinic

Patrice Carroll, M.S.

Social Worker and Director of PWS Services, Latham Centers, Brewster, MA

Janice Forster, M.D.

Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist, Pittsburgh Partnership – Specialists in PWS

Psychiatry Consultant to PWSA | USA and IPSWO, Pittsburgh, PA

Soo-Jeong Kim, M.D.

Department of Psychiatry, Seattle Children’s Hospital and Medical Center

Seattle Children’s Prader-Willi Syndrome Clinic; Seattle Autism Center - Medical Director. Seattle, WA

Elizabeth Roof, M.A.

Senior Research Specialist, Research Lab Director

Vanderbilt University, Prader-Willi Syndrome Initiatives, Nashville, TN

Deepan Singh, M.D., FAPA

Vice Chair, Ambulatory Psychiatry Services

Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY

Kim Tula, M.A.

Family Support Counselor, PWSA | USA, Sarasota, FL

Stacy Ward, M.S.

Director of Family/Medical Support and Special Projects, PWSA | USA, Sarasota, FL

The Foundation for Prader-Willi Research (federal tax id 31-1763110) is a nonprofit corporation with federal tax exempt status as a public charity under section 501(c)(3).

The mission of FPWR is to eliminate the challenges of Prader-Willi syndrome through the advancement of research and therapeutic development.

Copyright © 2020. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use. Privacy Policy. Copyright Infringement Policy. Disclosure Statement.