Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a rare, complex genetic disorder that affects many systems in the body and is present from birth. It is caused by the loss of function of specific genes on chromosome 15 that are normally active only on the paternal copy. PWS occurs in approximately 1 in 15,000 births and affects males and females, as well as all races and ethnicities, with equal frequency. It is recognized as the most common genetic cause of life-threatening childhood obesity.

PWS is best known for hyperphagia, a chronic and intense drive to eat that does not turn off, but PWS affects much more than appetite.

Common features include:

This video gives a brief overview of PWS:

The symptoms of Prader-Willi syndrome are likely due to dysfunction of a portion of the brain called the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is a small endocrine organ at the base of the brain that plays a crucial role in many bodily functions, including regulating hunger and satiety, body temperature, pain, sleep-wake balance, fluid balance, emotions, and fertility. Although hypothalamic dysfunction is believed to lead to the symptoms of PWS, it is not yet clear how the genetic abnormality causes hypothalamic dysfunction.

The symptoms of PWS change over time in individuals with PWS, and a detailed understanding of the nutritional stages of PWS has been published. Overall, there are two general stages of the symptoms associated with PWS:

Infants with PWS are hypotonic or “floppy”, with very low muscle tone. A weak cry and a poor suck reflex are typical. Babies with PWS usually are unable to breastfeed and frequently require tube feeding. These infants may suffer from “failure to thrive” if feeding difficulties are not carefully monitored and treated. As these babies grow older, strength and muscle tone generally improve. Motor milestones are achieved, but are usually delayed. Toddlers typically enter a period where they may begin to gain weight easily, prior to having a heightened interest in food.

An unregulated appetite (hyperphagia) and easy weight gain characterize the later stages of PWS. These features most commonly begin between ages 3 and 8 years old, but are variable in onset and intensity. Individuals with PWS lack normal hunger and satiety cues. They usually are not able to control their food intake and will overeat if not closely monitored. Food seeking behaviors are very common. In addition, the metabolic rate of persons with PWS is lower than normal. Left untreated or in an unrestricted environment, this combination of problems often leads to morbid obesity and its many complications.

In addition to obesity, a variety of other symptoms can be associated with PWS. Individuals usually exhibit cognitive challenges, with measured IQs ranging from low normal to moderate intellectual disability. Those with normal IQs usually exhibit learning disabilities. Other issues may include growth hormone deficiency/short stature, small hands and feet, scoliosis, sleep disturbances with excessive daytime sleepiness, high pain threshold, speech apraxia/dyspraxia, and infertility. Behavioral difficulties may include obsessive-compulsive symptoms, skin picking, and difficulty controlling emotions. Adults with PWS are at increased risk for mental illness. However, PWS symptoms vary in severity and occurrence among individuals.

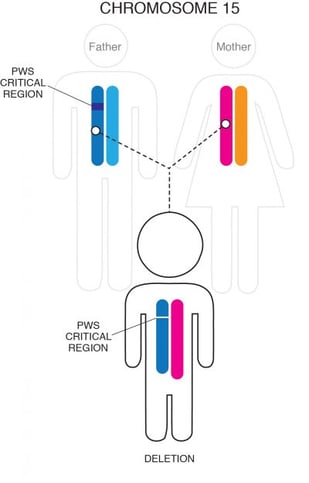

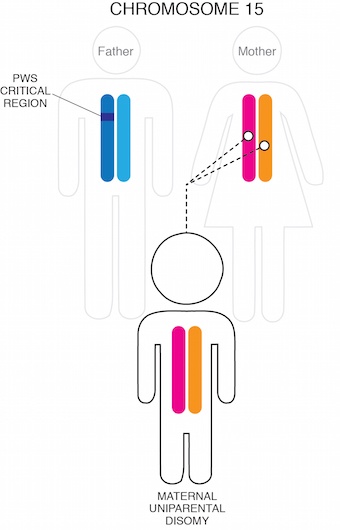

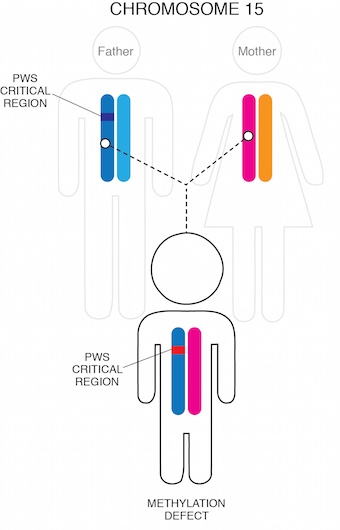

PWS is caused by a lack of active genetic material in a particular region of chromosome 15 (15q11-q13). Normally, individuals inherit one copy of chromosome 15 from their mother and one from their father. The genes in the PWS region are normally only active on the chromosome that came from the father. In PWS, the genetic defect causing the inactivity of chromosome 15 from the father (paternal chromosome 15) can occur in one of three ways:

Most often, part of the chromosome 15 that was inherited from the person’s father is missing, or deleted, in this critical region. This small deletion occurs in approximately 60% of cases and usually is not detectable with routine genetic analysis such as amniocentesis.

Another 35-40% of cases occur when an individual inherits two chromosome 15s from their mother and none from their father. This scenario is termed maternal uniparental disomy (UPD).

Finally, in a very small percentage of cases (1-3%), a small mutation in the Prader-Willi region causes the paternal chromosome 15 genetic material (although present) to be inactive.

The PWS region of chromosome 15 is one of the most complex regions of the human genome. Although there have been significant advances in understanding and characterizing the genetic changes associated with PWS, the exact mechanism by which lack of functional genetic material in this region leads to the symptoms associated with PWS is not understood. Scientists are actively studying the normal role of the genetic sequences in the PWS region and how their loss affects the hypothalamus and other systems in the body.

There may be some subtle differences in the characteristics of PWS based on genetic subtype: for example, those with deletions may be fair-skinned with light hair compared to other family members and may be more susceptible to seizures; those with PWS by UPD may be at higher risk for autism spectrum disorder and mental illness in young adulthood. Overall, however, there is considerable overlap between the different genetic subtypes. It is likely that the thousands of genes outside the PWS region, which exhibit normal variation between individuals, also contributes significantly to the variability in PWS symptoms between those with the disorder.

PWS is diagnosed with a blood test that looks for the genetic abnormalities that are specific to PWS – called a “methylation analysis.” A FISH (fluorescence in-situ hybridization) test identifies PWS by deletion, but it does not diagnose other forms of PWS. The methylation test will identify all types of PWS and is the preferred test for diagnosis. If a methylation test is done first, additional testing may be needed to determine whether PWS is caused by a paternal deletion, UPD, or an imprinting defect. In cases where an imprinting defect is suspected, blood may also be drawn from the parents.

PWS caused by deletion or UPD are random occurrences and generally are not associated with an increased risk of recurrence in future pregnancies. In the case of an imprinting mutation, Prader-Willi syndrome can reoccur within a family. Families with concerns about their risk for PWS should speak to a genetic counselor.

Currently, there is no cure for PWS, and most research to date has been targeted towards treating specific symptoms (see Diagnosis & Treatments). For many individuals affected by the disorder, the elimination of some of the most difficult aspects of the syndrome, such as the insatiable appetite and obesity, would represent a significant improvement in quality of life and the ability to live independently.

The Foundation for Prader-Willi Research advances research that will lead to new treatments for PWS with the goal of an eventual cure. A number of clinical trials are underway to evaluate drugs for treating specific aspects of PWS, and FPWR is supporting studies exploring genetic therapy for PWS.

There is a host of information on the Internet about Prader-Willi syndrome. One of the best places to start in developing a better understanding of the syndrome is to investigate the genetics.

Medline Plus is a US National Library of Medicine-sponsored site with a vast array of information to help understand genetics and genetic conditions. In addition, they have an information page specifically for Prader-Willi syndrome.

Gene Reviews, targeted to health professionals, contains detailed descriptions of diagnosis and management of Prader-Willi syndrome.

One of the largest sources of information regarding research can be found on PubMed. This is an up-to-date, searchable database of more than 16 million research abstracts, with links to articles in the medical literature. Current research on PWS can be found by searching with the relevant terms of (Prader-Willi, PWS, growth hormone, etc.)

The National Organization for Rare Disorders has a page on PWS in its Rare Disease Database that can be helpful in researching genetics and other aspects of PWS.

PubMed is updated frequently, and the abstracts are not always understandable to the layperson. FPWR monitors PWS research activity closely, and some of the most relevant studies are summarized in FPWR’s Research Blog. If you want to stay in close touch with the latest research, you might find it helpful to subscribe to an RSS feed of the Research Blog postings.

There are also government efforts to support research on rare diseases, including the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institute of Health.

The National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has excellent resources on genetics and can help educate those who are interested in the unique aspects of PWS research. One of the unique features of the site is a talking genetics glossary. In addition, the Department of Energy co-sponsors the Human Genome Project, and they have a general resource for genetics education regarding the human genome.

Note that over the years, PWS has been known as Prader-Willi, Prader-Labhart-Willi, or Prader-Willi-Fanconi syndrome, with Prader-Willi syndrome being most commonly used today. Prader-Willi syndrome is also sometimes misspelled as "Prada Willi" syndrome, "Prader Labhart Willy," or "Prader Willy" syndrome.

The Foundation for Prader-Willi Research (federal tax id 31-1763110) is a nonprofit corporation with federal tax exempt status as a public charity under section 501(c)(3).

The mission of FPWR is to eliminate the challenges of Prader-Willi syndrome through the advancement of research and therapeutic development.

Copyright © 2020. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use. Privacy Policy. Copyright Infringement Policy. Disclosure Statement.